Louise Bourgeois: In Torment There Are Islands of Silence. (Interview with Philip Larratt-Smith)

The interview with Philip Larratt-Smith, curator for The Easton Foundation, was conducted on the occasion for the exhibition ‘Louise Bourgeois. Soft Landscape’ at Hauser & Wirth (HK) in March 2025.

The Chinese article with a short overview with LB’s art is published on Modern Weekly Issue 1378, May 2025. /Interview & translation: Yiping Lin; Editor: Leandra

Modern Weekly: From 2002 to 2010, you worked as Louise Bourgeois’s literary

archivist. Could you briefly describe the job for us? What was it like working

for/with her? How did she live her life in the last decade of her life?

Philip Larratt-Smith: Bourgeois lived to work, and her last years were among the most productive in a long career. I was never that close to her, but we spend time together when I began working on my publication of the then-recently discovered psychoanalytic writings. I always enjoyed her sharp intelligence and demonic wit. She was seductive, flirtatious, acerbic, and quite ruthless in her relations with others, by which I mean she did not suffer fools gladly nor waste time on people who could not help her somehow. Someone said that there is no fat in Bourgeois’s writings, and the same is true of her way of being: Everything had its purpose.

What are some of the most fascinating aspects of Bourgeois’ art for you personally? How has working for her (re)shaped your understanding of her art?

I am drawn to the darkness and mystery of the work, to the anatomy of pain that is elaborated in it and also to its moments of reprieve. Bourgeois once wrote, “In torment there are islands of silence,” as if to say that perhaps this is all one can hope for. Sometimes when I look at her work I am reminded of what Francis Bacon said in the famous interview with David Sylvester about mounting a direct assault on the nervous system of the viewer. It acts so deeply and immediately that it produces an emotional and psychological reaction almost before you are aware of it.

We know that Bourgeois’ works have strong autobiographical underpinnings, reflecting her adolescent trauma with her father’s infidelity and her mother’s early death. She became deeply depressed when her father died, at which point she started going to psychotherapy and stopped having exhibitions for 11 years until 1964. Chronologically, this exhibition started with the Lairs and the Labyrinthine Tower exhibited in 1964 at the Stable Gallery. In the book published along with the exhibition “Louise Bourgeois – The Return of the Repressed,” which you curated in 2012, you call the sculptures the Lairs and the Labyrinthine Tower at the 1964 exhibition ‘soft landscapes,’ which is also the title of this exhibition in HK.

Can you talk about the decision to start with this moment of her career when you selected the artwork for this exhibition? In what sense are these works with ingrained emotional intensity soft? And how do we understand ‘soft landscapes’ in the context of this exhibition, which traversed nearly half a century—the second half of her long, prolific life?

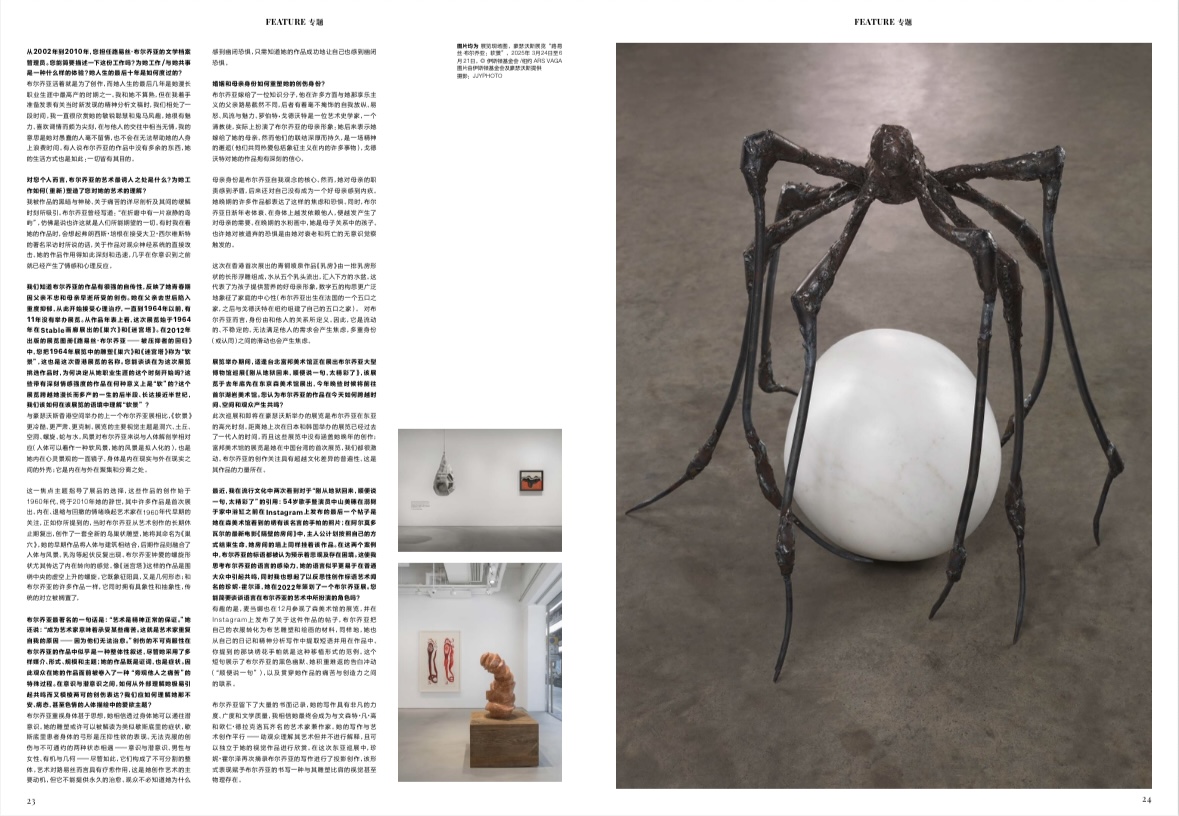

Compared to the previous show at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong, “Soft Landscape” is cooler, more sober and restrained. The prevailing iconography is one of holes, mounds, cavities, spirals, snakes, and water. Landscape for Bourgeois corresponded to human anatomy (the human body can be seen as a soft landscape, and her landscapes are anthropomorphic), but it is also a mirror for her inner psychic landscape. The body is the envelope between inner and outer reality; it is where they come together and where they move apart.

This thematic focus guided the selection of works in the show, which ranges from the 1960s until her death in 2010, and which features many works that have never been exhibited before. The mood of interiority, retreat, and withdrawal evokes the concerns of the early 1960s, when as you note Bourgeois emerged from a long hiatus in art making with an entirely new body of nest-like sculptures she called Lairs. Where her early work merged the human figure and architecture, the later work fused the figure with landscape. Undulations like the cleavage of breasts are repeated. Bourgeois’s beloved spiral form in particular conveys the sense of turning inwards. A work like Labyrinthine Tower is an ascending spiral around a central void. It is simultaneously phallic and geometric; like so many of Bourgeois’s works, it feels figurative and abstract at the same time, the traditional opposition is suspended.

One of the most famous sayings by Bourgeois goes: ‘art is a guaranty of sanity.’ She also says, ‘To be an artist involves some suffering. That’s why artists repeat themselves—because they have no access to a cure.’ Despite the myriad of mediums, forms, scales, and motifs, the insurmountableness of trauma seems to be a totalizing narrative in Bourgeois’ oeuvre, and her artworks are at once testimonies and symptoms. The audience is thus implicated in a peculiar process of ‘regarding the pain of others’ at the sight/site of her work. Located between the conscious and the unconscious, how can one understand her evocative and yet equivocal expressions of trauma from the outside? How should we understand the theme of amorous desires from her uncanny, morbid, and sometimes erotic portrayal of the human body?

Bourgeois privileged the body over the mind, believing that through it she gained access to her unconscious. Her sculptures may be read as analogous to the symptoms of the hysteric whose arched back is an expression of his repressed sexual desire. Insurmountable trauma meets the incommensurability of two states – conscious and unconscious, male and female, organic and geometric – that nonetheless make up an indivisible whole. Art had a therapeutic function for Louise, and this was her primary motivation for making it, but it does not provide a permanent cure.

The viewer doesn’t have to know why she feels claustrophobic, only that her work succeeds in making him feel claustrophobic too.

Philip Larratt-Smith: Bourgeois lived to work, and her last years were among the most productive in a long career. I was never that close to her, but we spend time together when I began working on my publication of the then-recently discovered psychoanalytic writings. I always enjoyed her sharp intelligence and demonic wit. She was seductive, flirtatious, acerbic, and quite ruthless in her relations with others, by which I mean she did not suffer fools gladly nor waste time on people who could not help her somehow. Someone said that there is no fat in Bourgeois’s writings, and the same is true of her way of being: Everything had its purpose.

What are some of the most fascinating aspects of Bourgeois’ art for you personally? How has working for her (re)shaped your understanding of her art?

I am drawn to the darkness and mystery of the work, to the anatomy of pain that is elaborated in it and also to its moments of reprieve. Bourgeois once wrote, “In torment there are islands of silence,” as if to say that perhaps this is all one can hope for. Sometimes when I look at her work I am reminded of what Francis Bacon said in the famous interview with David Sylvester about mounting a direct assault on the nervous system of the viewer. It acts so deeply and immediately that it produces an emotional and psychological reaction almost before you are aware of it.

We know that Bourgeois’ works have strong autobiographical underpinnings, reflecting her adolescent trauma with her father’s infidelity and her mother’s early death. She became deeply depressed when her father died, at which point she started going to psychotherapy and stopped having exhibitions for 11 years until 1964. Chronologically, this exhibition started with the Lairs and the Labyrinthine Tower exhibited in 1964 at the Stable Gallery. In the book published along with the exhibition “Louise Bourgeois – The Return of the Repressed,” which you curated in 2012, you call the sculptures the Lairs and the Labyrinthine Tower at the 1964 exhibition ‘soft landscapes,’ which is also the title of this exhibition in HK.

Can you talk about the decision to start with this moment of her career when you selected the artwork for this exhibition? In what sense are these works with ingrained emotional intensity soft? And how do we understand ‘soft landscapes’ in the context of this exhibition, which traversed nearly half a century—the second half of her long, prolific life?

Compared to the previous show at Hauser & Wirth Hong Kong, “Soft Landscape” is cooler, more sober and restrained. The prevailing iconography is one of holes, mounds, cavities, spirals, snakes, and water. Landscape for Bourgeois corresponded to human anatomy (the human body can be seen as a soft landscape, and her landscapes are anthropomorphic), but it is also a mirror for her inner psychic landscape. The body is the envelope between inner and outer reality; it is where they come together and where they move apart.

This thematic focus guided the selection of works in the show, which ranges from the 1960s until her death in 2010, and which features many works that have never been exhibited before. The mood of interiority, retreat, and withdrawal evokes the concerns of the early 1960s, when as you note Bourgeois emerged from a long hiatus in art making with an entirely new body of nest-like sculptures she called Lairs. Where her early work merged the human figure and architecture, the later work fused the figure with landscape. Undulations like the cleavage of breasts are repeated. Bourgeois’s beloved spiral form in particular conveys the sense of turning inwards. A work like Labyrinthine Tower is an ascending spiral around a central void. It is simultaneously phallic and geometric; like so many of Bourgeois’s works, it feels figurative and abstract at the same time, the traditional opposition is suspended.

One of the most famous sayings by Bourgeois goes: ‘art is a guaranty of sanity.’ She also says, ‘To be an artist involves some suffering. That’s why artists repeat themselves—because they have no access to a cure.’ Despite the myriad of mediums, forms, scales, and motifs, the insurmountableness of trauma seems to be a totalizing narrative in Bourgeois’ oeuvre, and her artworks are at once testimonies and symptoms. The audience is thus implicated in a peculiar process of ‘regarding the pain of others’ at the sight/site of her work. Located between the conscious and the unconscious, how can one understand her evocative and yet equivocal expressions of trauma from the outside? How should we understand the theme of amorous desires from her uncanny, morbid, and sometimes erotic portrayal of the human body?

Bourgeois privileged the body over the mind, believing that through it she gained access to her unconscious. Her sculptures may be read as analogous to the symptoms of the hysteric whose arched back is an expression of his repressed sexual desire. Insurmountable trauma meets the incommensurability of two states – conscious and unconscious, male and female, organic and geometric – that nonetheless make up an indivisible whole. Art had a therapeutic function for Louise, and this was her primary motivation for making it, but it does not provide a permanent cure.

The viewer doesn’t have to know why she feels claustrophobic, only that her work succeeds in making him feel claustrophobic too.

How do marriage and motherhood reconfigure her traumatic identity?

Bourgeois married an intellectual who in many ways was the opposite of her sensualist father Louis, with his frank self-indulgence, his rages, his dalliances, and his charm and charisma. Robert Goldwater was an art historian, a Puritan, and in fact a mother figure for Bourgeois: She later said she’d married her mother. Yet theirs was a deep and lasting bond, a meeting of minds (they shared a love of Symbolism, among many other things), and Goldwater believed deeply in her work.

Motherhood was central to Bourgeois’s conception of herself. Yet she felt conflicted about the responsibilities of motherhood and, later, guilty over not having been a good mother to her children. Much of her later work addressed these anxieties and fears. At the same time, Bourgeois felt in need of a mother as she grew frailer and more physically dependent on others. In the later gouaches, she is the child in the mother-child relationship. Perhaps her lifelong fear of abandonment was triggered by the unconscious awareness of her ageing and mortality.

The bronze fountain Mamelles, which is exhibited here in Hong Kong for the first time ever, consists of a long frieze of multiple breast-like forms, with five of the nipples spilling water into the basin below. This incarnates the ideal of the good mother that provides nourishment for her children, and more broadly the centrality of family symbolically represented here by the number five (Bourgeois was born into a family of five in France, and then had her own family of five with Goldwater in New York).

Identity for Bourgeois is defined in relation to the Other. It is therefore fluid and unstable. The inability to meet the demands of the Other generates anxiety. So too does the slippage between multiple shifting identities (or identifications).

This exhibition coincides with the large-scale museum tour in Asia “I Have Been to Hell and Back. And Let Me Tell You, It Was Wonderful,” opening in Taipei’s Fubon Art Museum in March, after traveling to Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum, and later in the year onto Hoam Art Museum in Seoul. How do you think Bourgeois’ works resonate today across time and space?

Thanks to this tour and the upcoming show at Hauser & Wirth, Bourgeois is having a moment in East Asia. It has been a generation since her last shows in Japan and Korea, which in any case did not include works she made in her last years; and the show at the Fubon Art Museum is her first ever, which is exciting.

There is something universal about Bourgeois’s concerns that transcends cultural differences. That is the strength of the work.

Recently, I saw two citations of “I Have Been to Hell and Back. And Let Me Tell You, It Was Wonderful” in popular culture: 54-year-old singer and actress Miho Nakayama’s last post on Instagram before drowning in her own bathtub is a photo of the embroidered handkerchief she had seen at Mori Art Museum; in Almodovar’s latest film, "The Room Next Door," a poster with the same line hangs on the wall of the protagonist (starred by Tilda Swinton) as she plans to end her life on her own terms. In both cases, Bourgeois’ slogan is perceived to foreshadow a sense of dismalness and existential conundrum. This led me to think about the affectivity of Bourgeois’ use of language, which is perhaps more easily picked up by the general audience, and also reminds me of Jenny Holzer, known for her reflexive use of slogans in art, who also curated an exhibition of Bourgeois in 2022. Can you briefly talk about the role of language in her art?

Interesting that Madonna visited the Mori show in December and posted on Instagram about this work as well.

Much as Bourgeois turned her clothes into materials for her fabric sculptures and drawings, she also lifted phrases from her diaries and psychoanalytic writings and used them in her works. The embroidered handkerchief you reference is an example of this form of cannibalization. The phrase exhibits Bourgeois’s sense of black humour, her inveterate confessional impulse (“let me tell you”), and the link between suffering and creativity that pervades her work.

Bourgeois left a vast written record, and the strength, range, and literary quality of her writing is such that I believe she will eventually take her place as an artist-writer of the first rank, alongside Vincent Van Gogh and Eugène Delacroix. Her writings are a parallel body of work – they shed light on but do not explain her art, and they can be appreciated independently of her visual output.

For the touring exhibition, Jenny Holzer once again created projections using excerpts from Bourgeois’s writings, a formal device that gives the writings a visual and even a physical presence alongside Bourgeois’s sculptures.

Bourgeois married an intellectual who in many ways was the opposite of her sensualist father Louis, with his frank self-indulgence, his rages, his dalliances, and his charm and charisma. Robert Goldwater was an art historian, a Puritan, and in fact a mother figure for Bourgeois: She later said she’d married her mother. Yet theirs was a deep and lasting bond, a meeting of minds (they shared a love of Symbolism, among many other things), and Goldwater believed deeply in her work.

Motherhood was central to Bourgeois’s conception of herself. Yet she felt conflicted about the responsibilities of motherhood and, later, guilty over not having been a good mother to her children. Much of her later work addressed these anxieties and fears. At the same time, Bourgeois felt in need of a mother as she grew frailer and more physically dependent on others. In the later gouaches, she is the child in the mother-child relationship. Perhaps her lifelong fear of abandonment was triggered by the unconscious awareness of her ageing and mortality.

The bronze fountain Mamelles, which is exhibited here in Hong Kong for the first time ever, consists of a long frieze of multiple breast-like forms, with five of the nipples spilling water into the basin below. This incarnates the ideal of the good mother that provides nourishment for her children, and more broadly the centrality of family symbolically represented here by the number five (Bourgeois was born into a family of five in France, and then had her own family of five with Goldwater in New York).

Identity for Bourgeois is defined in relation to the Other. It is therefore fluid and unstable. The inability to meet the demands of the Other generates anxiety. So too does the slippage between multiple shifting identities (or identifications).

This exhibition coincides with the large-scale museum tour in Asia “I Have Been to Hell and Back. And Let Me Tell You, It Was Wonderful,” opening in Taipei’s Fubon Art Museum in March, after traveling to Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum, and later in the year onto Hoam Art Museum in Seoul. How do you think Bourgeois’ works resonate today across time and space?

Thanks to this tour and the upcoming show at Hauser & Wirth, Bourgeois is having a moment in East Asia. It has been a generation since her last shows in Japan and Korea, which in any case did not include works she made in her last years; and the show at the Fubon Art Museum is her first ever, which is exciting.

There is something universal about Bourgeois’s concerns that transcends cultural differences. That is the strength of the work.

Recently, I saw two citations of “I Have Been to Hell and Back. And Let Me Tell You, It Was Wonderful” in popular culture: 54-year-old singer and actress Miho Nakayama’s last post on Instagram before drowning in her own bathtub is a photo of the embroidered handkerchief she had seen at Mori Art Museum; in Almodovar’s latest film, "The Room Next Door," a poster with the same line hangs on the wall of the protagonist (starred by Tilda Swinton) as she plans to end her life on her own terms. In both cases, Bourgeois’ slogan is perceived to foreshadow a sense of dismalness and existential conundrum. This led me to think about the affectivity of Bourgeois’ use of language, which is perhaps more easily picked up by the general audience, and also reminds me of Jenny Holzer, known for her reflexive use of slogans in art, who also curated an exhibition of Bourgeois in 2022. Can you briefly talk about the role of language in her art?

Interesting that Madonna visited the Mori show in December and posted on Instagram about this work as well.

Much as Bourgeois turned her clothes into materials for her fabric sculptures and drawings, she also lifted phrases from her diaries and psychoanalytic writings and used them in her works. The embroidered handkerchief you reference is an example of this form of cannibalization. The phrase exhibits Bourgeois’s sense of black humour, her inveterate confessional impulse (“let me tell you”), and the link between suffering and creativity that pervades her work.

Bourgeois left a vast written record, and the strength, range, and literary quality of her writing is such that I believe she will eventually take her place as an artist-writer of the first rank, alongside Vincent Van Gogh and Eugène Delacroix. Her writings are a parallel body of work – they shed light on but do not explain her art, and they can be appreciated independently of her visual output.

For the touring exhibition, Jenny Holzer once again created projections using excerpts from Bourgeois’s writings, a formal device that gives the writings a visual and even a physical presence alongside Bourgeois’s sculptures.